This Wednesday the words are over at WiseWebWoman's blog. As I threatened to do, I cleaned the slates of February's unused words and now start anew with:

Wardrobe

Silhouette

Sergeant

Dispensation

The photo andPlacebo

Displeasure

Sympathy

Discretion

And I used 1 (one!) word in this part of the story, Displeasure

. More is to follow, but it is long enough for many days. I do not know why I have a tendency to write such long tales from some of the words. It just happens. I hope you enjoy reading, and as always please correct my English!

Remember to go back, read other peoples' stories there or follow their links back. And please place a comment after reading. Challenges like this one thrives on interaction.

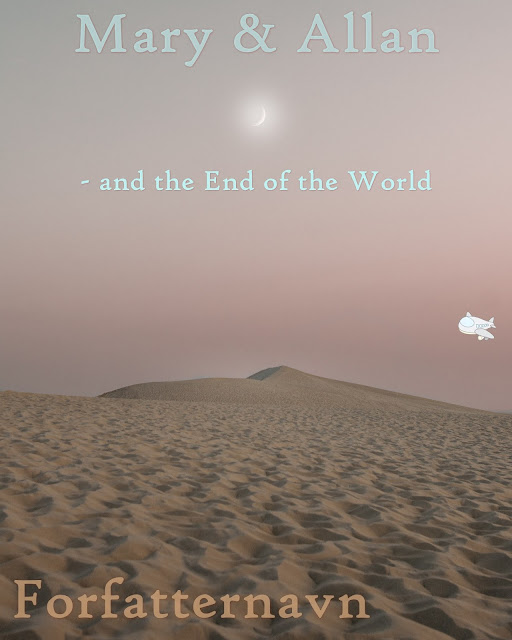

Back in January 2020, I wrote a long story about Allan, Mary and the end of the World. It had a spin-off in June about Fr. Paul, but in between these two parts a lot happened. All the chapters can be read in one long go by choosing the tab "Mary & Allan" in the top of this blog.

Here's a bit of what happened to Mary, Allan and their co-survivors after we left them on the white cliffs of Møn.

Next day the discussion continued.

It turned to ways and means of finding more people.

"The plane is visible day and night. This is good, but should we search? and if yes, then where?" Tom asked.

"Yes we should," Mary said. "The more people, the better we're off in the long run."

"But we risk depleting our foodstuff if we find many," Granny T protested.

"Numbers, skills etc. are more important. We will survive. The green stuff is already growing both in the floating garden and aboard the plane. It won't be long before we can harvest the first crops. Besides we still don't have anybody with real, old fashioned farming skills!"

"My question still stands," Tom. "Where to look."

"Where?" Allan said. "Underground, mines and such. Everybody except for us plane-people survived underground. And we cannot guess where planes will have landed, but mines have to stay where they are."

"And now we know where we are," Tom said, "maps and equipment in the plane will be of big help. I can still plot a course by hand and use a compass and the other non-electrical equipment of the plane."

"And we can learn," Mary added.

"Wieliczka," Eva said.

"Say what?" Tom said

"Wieliczka," Eva repeated. "It's a salt mine in Poland. Not in use, but a museum. It's fantastic, caves, even a church carved in salt-stones of different colours. I bet it was filled with visitors when the wave hit! I went skiing in the Tatry-mountains near there more than once."

"And Goslar, Germany. There's one like it, only not salt, iron or some such ore. That one is even closer," James, the actor, said.

"Show me those places on the map," Tom said rolling out a big, old map of northern Europe on a table.

Eva and James showed him where. and Tom bade Robert and Eva come and help him do the maths. They drew two tentative courses, one Goslar - Wieliczka, one the other way round.

"Let's end up in Goslar," Allan said. "The Tartrys for all their immense beauty was not renowned for their fertile grounds."

That motion was shared by most of the collected group. Mona agreed, and her opinion counted, as she was the only farmer at hand. "We have to go south," she said. "And from Wieliczka that means mountains, a hazardous thing to brave, but going back west and a bit north from there to Goslar will of course set us somewhat back, but the lessening hazards from partly underwater mountain ranges should more than make up for this."

"I agree," Tom said with marked displeasure. "The plane is amazingly seaworthy what with the outriggers and so on. But jagged mountaintops would not be good."

***

The next morning they left the white cliffs of Møn and set the course due east. The life went on much as it used to, the settled routine of the two communities intermingling almost seamlessly. The most visible differences were by lanterns on the floating village by night and masts and pennants on the plane by day. Learning and teaching took place all over, in the open spaces of the floating village, when the weather was fine, inside the huts and on board the plane when it rained, as it did most of the time still. All took turns rowing, and everybody was swimming or taught how to by the two young doctors and Father Paul. They had to keep fit.

One evening Tom said: "Tomorrow we have to go slowly. I need to know exactly how far east we have come so as to hit the rivermouth as shown in the course diagrams. All who wants to, can have a go at the sextant. But I want the 12 noon spot!"

"Aye, aye captain." Robert said standing at attention.

"Yes, Tom said after reading the Sun, conferring with the charts, and as many as wanted to try and understand course plotting, "now we go South. We have to hit the river complexes leading to the mine," he said, pointing to Oder on the map, and following it and Weichsle and Dunajec to Wieliczka. "The rivers go right through the cities of Stettin, Wroclaw, Kattovice and Kracow down to the salt mine here. Of course the cities are not there any more, but the land will still be level as opposed to outside the watercourses.

After a few days going south, people armed with stakes were once again at their places in the hauling boats and every day they stopped at a quarter to noon to let Tom do his magic. Many of the others tried their hand at it, and became quite adept at knowing just where they were.

They worked their way slowly south and east, keeping over the old waterways. It still rained every day. Mornings and evenings were mostly clear, the downpour beginning at around ten and going steadily until six or seven in the evening. Ben made some lead lines for the staking of the depth, this was easier, faster and less dangerous than the poles, giving longer reach and less risk of falling overboard. Still they found no ground below.

They turned more towards east and next day mountains slowly grew up from the waters south and east of them. "The Tatrys," Eva said with a satisfied expression.

"Yes? Do you recognise them? Mountains should not be bothered overmuch by the wave," Allan said.

"I'm not sure, but that one could be 'Silvertop'," Eva said. "The mine should be a little closer to the mountains, away from the river," they agreed

They rowed slowly, testing the depths, this close to the mountains they saw no need in running unnecessary risks.

Robert yelled: "Something down here. Stop!" And the back up crew hurried to the small boats behind the plane and rowed the other way. This of course stopped the plane, and the floating village was alerted and also came to a halt.

"What is down there, and how far?" Tom asked. They freed the life boat, and slowly rowed back and forth, testing the depth. "Here," Robert yelled. "Almost at the end of the rope ... far down. and only here. Slowly forwards, please," he asked, and the rowers rowed carefully forwards. Robert threw the line again and again, but nowhere else did it reach anything. "Maybe an immersed mountaintop?" Robert mused.

"I think not", Tom said "The mountains rise fairly suddenly here." Eva nodded.

"It could very well be some mine-related thing," Tom said. "It should be here, very near. Let's row the boat closer to the mountain range. If somebody survived somewhere underground they'll have to have come out, and the mountains would be the logical place to go."

"Should we risk a boat?" Cordelia asked. "Should we not stick together?"

"I think you're right Cordelia," Robert said. "No use risking anything. They might be desperate if they just sit on a mountainside watching the waters rise and rise. And desperate people can be dangerous as well we know," he said with a lopsided smile.

They were extra careful throwing the lines at regular intervals. Robert gave over his post to Lisa, and she in turn was replaced by Henny.

Henny was the one who finally struck ground. "Bottom here!" she called; only to be echoed seconds later by Ben in the other boat.

Slowly they proceeded. Always nearer the mountain range with the floating village bringing up the rear. When they had to stop for the night they scanned the mountainside using binoculars, but nothing could be seen.

In the night, Robert thought he saw a light flickering far away, he woke up Tom and Hank and had them look. They marked where they had seen the flicker, for armed with binoculars they thought they caught the flicker of a fire between two mountain tops.

In the morning they steered after the fire, and proceeding with care, they sailed closer to the gap between two mountain tops, and saw the remnants of a dying fire and a flag pole with a red shirt hanging limp and damp in the murky daylight.

"Back up!"Hank yelled. "It's a trap!" The ones in the pulling boats immediately stopped rowing, backing up and then hoisting their oars while the crew in the two smaller boats behind the plane rowed for dear life, stopping, then painstakingly slowly pulled the plane backwards.

A mixture of assorted projectiles rained down over the crew in the two boats. Stones, mine struts, and various debris came down from the mountain tops. But their aim was miserable, and the throws lacked speed and precision.

Eva suddenly poked her head through the plane door and shot a string of harsh-sounding syllables at the mountains.

She was answered from above. Only one word, but understandable for the people in the boats. "Nie - no"

Eva spoke again, this time helped by the megaphone from the plane.

Another voice answered from the other mountain top. This one plaintive, longer. Back and forth the conversation went. The plane stopped well out of throwing range and all the boats gathered round the plane, where Eva told what she had found out.

"They say they do indeed come from the salt mine. They have nothing more to eat and they are armed. With what, I did not understand. Maybe pikes, maybe other strange things from the salt mine."

"Desperate," Robert nodded. "And maybe dangerous."

"We have to stay out of range of even a gun, then" Allan said, "but still within hailing distance."

One small boat sailed off to the village and they pulled closer to the plane after hearing the news.

"Theirs is the untenable situation," Hank said. "We can just leave them. Or at least they must think so. They cannot get close to us without us hearing or seeing them. But that said, we must not become careless. They are desperate, we don't know how many they are, and we have no weapons with which to defend ourselves."

"I'd say they have no weapon either," Hank said. "They have not been shooting. and everything must have been pulled over here from the mine by manpower. If that unknown thing yesterday was indeed the mine, as we suspect, they have walked quite a distance carrying stakes and stones. Maybe they have even been fighting among themselves. They must be hungry by now."